Their self-designation is udee, uddee, udehe (Udihe). They are also named Kekar (after a large tribe). In literature, the names Orochon and Taz have been used. Orochon comes from the word Oron-'reindeer' and means 'reindeer-breeders', although the breeding of reindeer was not an occupation particularly characteristic of the Udeghes. The name Taz for the southern group of the people comes from Chinese, where Ta-tzy means all the peoples of the Lower Amur. Their self-designation is udee, uddee, udehe (Udihe). They are also named Kekar (after a large tribe). In literature, the names Orochon and Taz have been used. Orochon comes from the word Oron-'reindeer' and means 'reindeer-breeders', although the breeding of reindeer was not an occupation particularly characteristic of the Udeghes. The name Taz for the southern group of the people comes from Chinese, where Ta-tzy means all the peoples of the Lower Amur.

The Udeghes are scattered over an extensive area in the Khabarovsk region and in the Ussuri taiga, in the northern part of the Primorye region. They have no compact settled area. They live in the neighbourhood of the Nanais and the Nivkhs and in places are mixed with them. There are nine ethnically pure Udeghe settlements.

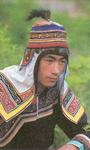

Anthropologically the Udeghes are Mongoloid, belonging to the Baikal type.

The Udeghe language belongs to the southern group of the Manchu-Tungus languages and is divided into three dialects with numerous vernaculars. The closest linguistic relatives are Orochis.

The origin of the Udeghes is not quite clear and causes dispute to this day. There are two hypotheses: one that their origin is to the north, the other, that it is to the south. The first is confirmed by their cultural closeness to the Orochis and the obvious connection with the ancient local Paleo-Asian population. But the Udeghes have also conspicuous southern features which stem from Manchuria and China. Some Ainu and Tungus (Evenk) components have also been noted. The oral traditions of the Udeghes also indicates a complex origin. In the 19th century, they used to live in eight territorial groups over a vast area between the rivers Ussuri and Amur and Sea of Japanes. They had no common ethnic identity. In the 19th century the Udeghes were generally not distinguished from the Orochis. Only towards the end of the century did V. Margaritov, and especially S. Brailovsky, who conducted the 1897 census, distinguish the southern group from the Orochis. S. Brailovsky was the first to suggest that the people be called by their own self-designation, Udeghes. The River Botch was suggested as a boundary. So, in 1897, the area of the Udeghes extended to the southern tributaries of the Ussuri and along the coast as far as Nakhodka. At that time, Udeghes could also be found on the Hungar, the Tunguska and other tributaries of the Amur. Since 1860, when the whole Ussuri region was incorporated into the Russian Empire, the Udeghes have been part of Russia.

Unlike their neighbours, the Nivkhs, Nanais and other settled peoples on the Amur, the Udeghes' way of life was closely connected with their taiga forest and hunting. This necessitated a more mobile lifestyle. In spite of their nomadic life the Udeghes and Orochis did not raise reindeer, a fact which distinctly separated them from many other taiga peoples. The primary object of hunting was gaining furs and meat, though obtaining the antlers was also essential. The antlers were sold to the Chinese. The Chinese also bought the root of the ginseng plant which grew in the Ussuri taiga and searching for this plant was one of the vital occupations of the Udeghes. Unlike other Amur peoples, fishing played a less important part in their life. And only the southern Taz, following the example of the Chinese, tilled their fields in the coastal river basins.

It was customary for the Udeghes to live dispersed, in separate families, and to resettle often, according to the areas being hunted. Influenced by the Nanai, in the 19th century the first permanent settlements began to grow on the River Anyui. The Taz were settled. More permanent Udeghe settlements developed after the 1930s, when the forcible collectivization of households began. This was completed in about 1937. At present there are nine Udeghe settlements all located some distance apart. Resettlement caused many families to have to change their mode of living, for example, from hunting to land cultivation and animal breeding. This transformation was hastened by the diminishing area of the hunting grounds, caused by the felling of timber (especially in the Primorye region), This was the reason for the constant resettling of the Udeghes from their native areas (where about 43% of the people lived), into the Khabarovsk region.

Udeghe habitats were incorporated into Russia in 1860, but for a long time the real rulers were the Chinese traders of furs and ginseng, to whom many Udeghes were hopelessly indebted. Russian peasants began to settle in the Ussuri region sometime after 1883, but this colonization did not much concern the Udeghes, who roamed deep in the forests. On the contrary, according to the observations of many travellers of that time, the Udeghes' attitude towards the Russians was remarkably friendly, since the Russians displaced the exploitative Chinese traders. The Russian influence on Udeghe folk culture was also less than that on other Amur peoples. The women's folk costume, as well as the men's hunting garb and equipment, were relatively well preserved.

However, against this background, a drastic deterioration in spiritual culture took place, reflected most in the language. In 1979, the Udeghe language was considered a mother tongue by only 31% people. It was spoken by 37.5% of the people. At the same time, Russian was spoken fluently by as many as 94.1% of the Udeghes, the data in 1970 was 55.1%, 63.8% and 89.9% respectively. Primary education in the mother tongue began as early as 1931, when the first school textbooks in the Udeghe language appeared. As elsewhere in the Soviet Union, this process had subsided by the late 1930s and another attempt to create a new Udeghe alphabet was made only in the late 1970s. Nowadays, the mother tongue is again taught in some schools, but only as an optional subject. The status of the Udeghe language measured against Russian is very low, and the prospects of it being taught in the first forms of Russian-language boarding schools are not very promising. The only Udeghe writer of any renown is Djansi Kimonko. Other artistic activities have been limited to a few traditional branches of folk culture (leather and woodwork and embroidery) and amateur art in clubs. This has all developed according to standard regulations, ignoring any deeper knowledge of folk traditions. At present, the best known amateur art group is the ensemble "Giva". 55.1%, 63.8% and 89.9% respectively. Primary education in the mother tongue began as early as 1931, when the first school textbooks in the Udeghe language appeared. As elsewhere in the Soviet Union, this process had subsided by the late 1930s and another attempt to create a new Udeghe alphabet was made only in the late 1970s. Nowadays, the mother tongue is again taught in some schools, but only as an optional subject. The status of the Udeghe language measured against Russian is very low, and the prospects of it being taught in the first forms of Russian-language boarding schools are not very promising. The only Udeghe writer of any renown is Djansi Kimonko. Other artistic activities have been limited to a few traditional branches of folk culture (leather and woodwork and embroidery) and amateur art in clubs. This has all developed according to standard regulations, ignoring any deeper knowledge of folk traditions. At present, the best known amateur art group is the ensemble "Giva".

|

State

State  Nations of Russia

Nations of Russia